Payjoin for a Better Bitcoin Future

October 31, 2023

Payjoin is a protocol that uses a simple, clever trick in the way Bitcoin creates transactions to solve many of its problems at once. It was created to solve Bitcoin’s biggest privacy problem, but can also assist with its scaling problem, and help people save on fees. It’s particularly compatible with Lightning Network Nodes, as it currently has a liveness requirement for the receiver, meaning they must be online at the moment they are being sent money (just like a Lightning Node). In the future, even this requirement will be eliminated and it can be used offline. It can be easily integrated into wallets, it can be used to open many lightning channels at once, and it’s usage can be made passive, so that you can receive the benefits of Payjoin without even knowing you’re using it. The privacy benefits of payjoin cascade, so that everyone would see privacy gains even if only a minority of people used it. And, perhaps best of all, payjoin doesn’t require a hard or soft fork. It can be and is used on Bitcoin today, and it could be used on Bitcoin from the very first version of the software.

Payjoin is a derivative of Coinjoin, which is an older, more interactive protocol, meaning the user must be heavily engaged with it to use it, which necessarily drives down usability and inhibits adoption. Somehow, despite this, Coinjoin has seen much higher adoption than payjoin so far, despite the more obvious benefits and ease of use with payjoin. A complex, unclear path forward for developers inhibits adoption by wallet software.

Payjoin has been around for a few years, and given:

- The many benefits listed above

- The ability for a passive, nonintrusive user interface

- The simplicity for wallet providers to integrate it

Why is adoption so low?

Especially compared to the far more interactive, difficult to use, and expensive Coinjoin protocol?

In this article, we’ll look at current attacks on Bitcoin privacy, the history of payjoin from the perspective of privacy, how it works and how it can provide so many benefits with no changes to Bitcoin, and the current state of adoption. If payjoin can radically improve privacy, scaling, and fee issues with Bitcoin, the low effort required for wallets to integrate it would be well worth it.

Why Privacy Matters for Bitcoin

Before discussing the importance of payjoin, we must understand the importance of privacy. If you don’t need convincing on this front, feel free to skip down to the history and explanation of payjoin.

In Western democracies, the prime importance of privacy is difficult to communicate, as its benefits still seem invisible to people. It is harder to convincingly explain to someone why privacy matters (especially in the face of higher cost or greater inconvenience) if they’ve never felt the often terrible consequences of bad actors having too much information about them, perhaps because it requires people to think long-term about the consequences of these invasions.

Still, privacy seems to be something more and more people want in theory, but they typically do little to achieve it unless the barriers are extremely low and convenient. Therefore, technologies that wish to protect people’s privacy should be designed to do so with minimal requirements for interaction and inconvenience for the user.

Fungibility

Privacy is not the only problem payjoin can help solve, but it is the problem it was created to solve. The lack of privacy by default on Bitcoin has long been lamented, and one taken very seriously in the Bitcoin community. Bitcoin was designed to be directly peer-to-peer and censorship resistant. But the ability to track owners of future payments once coins have been linked to an identity allows for discrimination. This destroys fungibility – or the degree to which one of a currency’s individual units are indistinguishable from another of the same unit – which is one of the primary properties of a good money.

If buyers can be tracked, not only can coins that are currently owned by illicit actors be rejected, but coins that have ever been used for illicit purposes can be marked as such and be rejected by merchants, nevermind whether the current owners obtained them through perfectly legitimate means. Imagine not being able to buy milk at the grocery store because the dollars you have were once-upon-a-time used to buy drugs, would it be fair to you to be discriminated against by having them say “your money is no good here”? Should you be punished for someone else’s crime? And what would that do to how you treat those dollars? It would make them worthless as your spending power is diminished by owning them, and make some dollars (the “non-tainted” dollars) more valuable than other dollars, which of course shouldn’t make sense. One dollar should always equal one dollar, no matter what individual one dollar bill is used to represent it, or the ability of the dollar to do its job of transferring value is impeded.

The Criminal Myth

It is often said by Bitcoin and privacy detractors that privacy is for criminals. This is the familiar “if you aren’t doing anything wrong, you have nothing to hide” logic, which is easily refuted:

- Few people would be okay with an internet live stream of them taking a shower or using the bathroom being broadcast. Is that because it’s wrong? This is to point out that everyone has something to hide, and hiding things isn’t inherently wrong.

- More broadly, the government is charged with providing the legal basis for what’s wrong, but that definition is always subject to change. If people aren’t free to have privacy, then they really aren’t free at all, as their actions will be severely restricted by perceived social, if not governmental, restrictions. People are judged and attacked for doing perfectly legal things by others all the time. Privacy is the power to choose who you reveal yourself to.

Aside from this naive and self-evidently illogical argument, criminals, unlike most law-abiding citizens, are willing to accept high costs to obtain privacy, so measures to hurt privacy-by-default hurt regular people far more than they hurt criminals. This would be the case even if governments weren’t doing a poor job of actually using their new privacy-restricting measures to actually catch criminals en masse, but instead to “pick and choose” and selectively spy on the citizenry at their will. If a citizen says something those in power don’t like, and what those in power don’t like is always in flux, it can selectively decide to target and hurt them.

Finally, the desire for privacy isn’t merely the fear of government overreach. It is a practical safety or reputational concern. If someone can find out how much money you have and where you live, how hard is it to steal from you? Now consider the number of places you entered your address, payment details, pictures, on the internet. Do you trust every one of those sites to keep your information secure? You shouldn’t, because even the best fail, and criminals are paying large sums of money to hackers who exploit weaknesses for this valuable information.

Privacy and Democracy

A prerequisite to control in any totalitarian state is knowledge of the speech, access to information, and financial activity of its citizens. Without it, it can’t know what to attack, shut down, or manipulate to advance its narrative or further its control. If it doesn’t reliably have access to this information, it becomes difficult to target citizens on a whim. In totalitarian societies of the past, such as the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, privacy was eroded by ensuring the indoctrination of family members who would report on unfavorable opinions in private conversations, destroying webs of trust in families. When this same erosion of privacy occurs with money, its effects can be even more powerful than with speech. Cutting off the source of funding can be a very effective means of disbanding political dissent.

Bitcoin Privacy is Under Attack

Never waste an opportunity afforded by a good crisis

– Attributed to Nicollo Machiavelli

It is in the name of combating criminals, in this case Hamas terrorists, that new regulation is opportunistically being proposed to make privacy-preserving methods in Bitcoin illegal.

On October 10, 2023, an article was published by the Wall Street Journal reporting that Hamas acquired $130 million dollars of funding by means of cryptocurrency. One week later, senator Elizabeth Warren wrote a letter to President Biden urging him to address questions regarding his administration’s response to the “use of cryptocurrency by terrorist organizations” by October 31, citing the WSJ article as evidence of the urgent need for such regulation. The letter obtained the signatures of 29 of the 100 senators, and 76 members of the House. Curiously, on October 19th, just two days after the letter was sent, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network published a proposal for regulating cryptocurrency mixing due to the risk of money laundering. It lists, among the methods used to obscure transactions:

Using programmatic or algorithmic code to coordinate, manage, or manipulate the structure of a transaction: This method involves the use of software that coordinates two or more persons’ transactions together in order to obfuscate the individual unique transactions by providing multiple potential outputs from a coordinated input, decreasing the probability of determining both intended persons for each unique transaction.

This definition includes Coinjoin and Payjoin, although using algorithmic code is broad enough to include any transaction, and therefore justify at-will censorship.

But the WSJ article, which provided the sentiment for the letter and attempted to justify the regulation, horribly misinterpreted the data – the actual dollar amount that was connected with Hamas was $450,000. Cryptocurrency is nowhere near a major source of Hamas’ funding. Hamas itself explicitly stated that they did not want funding via Bitcoin due to its traceability.

The irony of the proposed regulation, then, is that its effects will be minimally impactful to the terrorist organization that is the justification for its existence, but maximally impactful to everyone else who wants to use Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.

There can be little doubt that the battle for the right to privacy in Bitcoin has arrived in the U.S., and it has predictably masked itself in the guise of national security against foreign adversaries. It’s more important now than ever to understand the need for and use of privacy-preserving techniques on Bitcoin to combat the ongoing attempts to chip away at it.

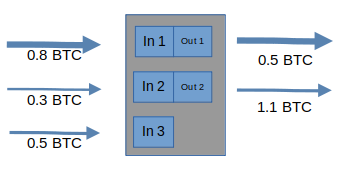

1. How Transactions Work

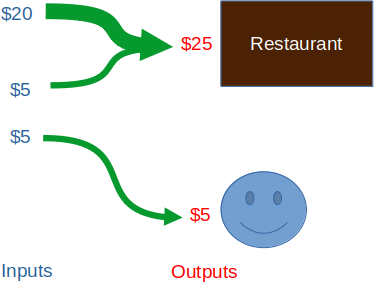

To understand the need for payjoin and how it works, it’s crucial to understand how transactions work. Each transaction in Bitcoin is a combination of inputs and outputs. Outputs define which public key or “address” the bitcoin is being sent to. Inputs define which “sources” or previous outputs are used in creating the new outputs for a transaction. It is helpful to think of this as an analogy to how we use different denominations of cash to pay for things. Imagine you need to pay $25 to a restaurant for dinner, plus a $5 tip for the waiter, for a total of $30 (these are your outputs, two different “chunks” of money going to two different people – the restaurant and the waiter).

How would you pay it? Let’s say you have the following bills available (these are your inputs):

- One $20

- Two $10’s

- Six $5’s

To construct this transaction, you could use one $20 bill and two $5 bills, one being for the waiter:

Note one important way in which our cash analogy breaks down: the $20 and the $5 merge into one “bill”. This would be more analagous to melting individual pieces of gold into one bigger piece in order to be able to pay the exact amount required, instead of handing over multiple pieces. Bitcoin allows us to split and merge inputs however we’d like to create the appropriate output.

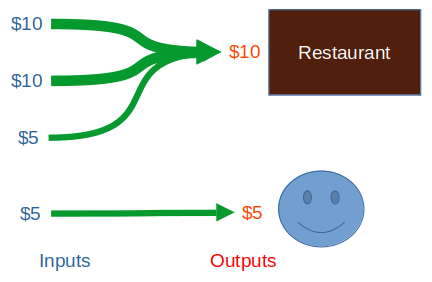

You might also use two $10 bills and two $5 bills like so:

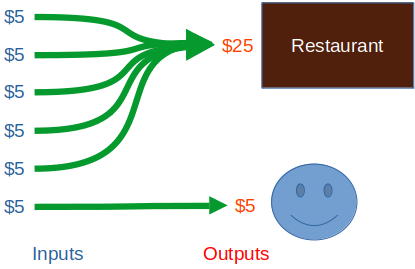

You could even use your six $5 bills:

Before they’re spent on something, the individual bitcoin “bills” you have are called unspent transaction outputs, or UTXOs. This name is confusing at first, but makes perfect sense if you think about it. They are the “results” (outputs) of transactions that haven’t yet been used up by other transactions. A transaction output that is unspent is a transaction output that you can spend. Therefore, in effect, UTXOs become like the bills of cash in your wallet. After they’re spent, they become inputs to another transaction’s outputs (the cash in someone else’s wallet), and are no longer spendable by you, but the record of the fact that you spent that bill to them remains on the blockchain.

Unlike cash, for a Bitcoin transaction to be valid, we need the approval of the sender. This is done with the sender’s digital signature, which serves as proof of their intent to spend the coin. A valid signature (that is, a signature corresponding to the address of the UTXO) needs to be present on each UTXO that the sender is trying to spend as an input to a new transaction. The presence of a signature “unlocks” the UTXO and signals that it was its owner’s intent to spend it in the proposed transaction.

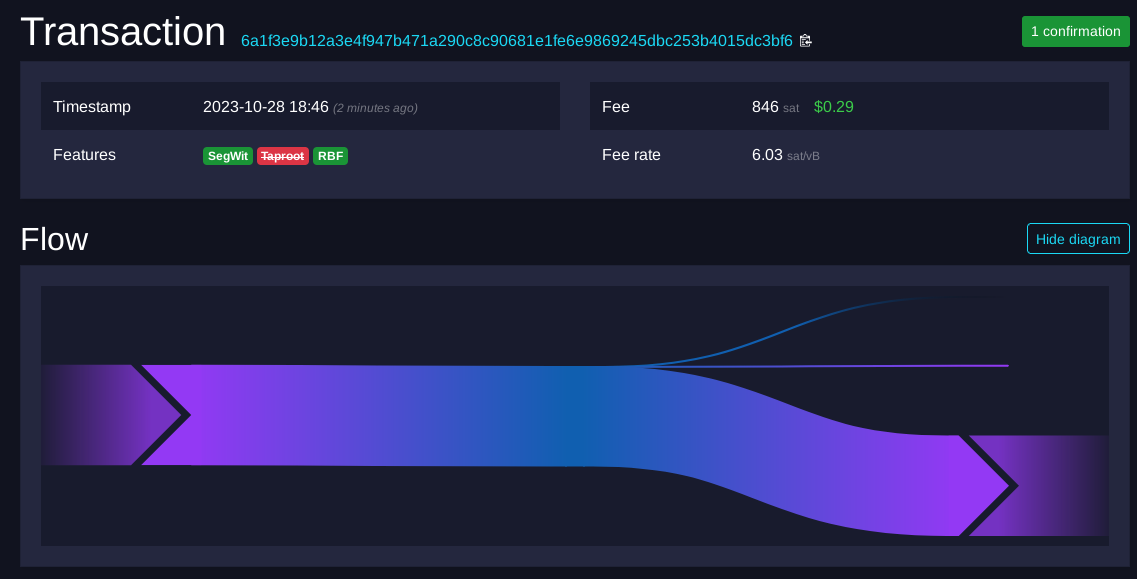

Here is an example of a real transaction that had 1 confirmation while writing this:

As we can see, the above transaction consumes one input and creates two outputs, one being the actual payment, and the other almost certainly being change sent back to the spender. A fee equal to the sum of the inputs minus outputs is also paid to the miner.

This “UTXO model” is very powerful. Since every transaction has inputs and outputs, and since the outputs of one transaction become the inputs of another transaction later, we end up with a long chain of transactions, and are able to track bitcoins’ transfer of ownership from transaction to transaction all the way back to a miner. Since Bitcoin has a limited supply, and derives its crucially non-inflationary properties from this fact, it’s important to be able to audit how much is in circulation or “unspent” at any given time, which the UTXO model allows for.

This is the crux of the privacy problem with Bitcoin. Every transaction has a history. All the bitcoin that came to you and anywhere you send it to can be easily tracked. The system was explicitly designed to support this, albeit not with the intention of tracking individuals. In this system, your only true bet is to never link your identity with your public key, which, in our age of mass surveillance, can be very hard.

The Historical Origins of Payjoin

Satoshi’s Modest Mistake

When Satoshi published the whitepaper in 2008, he recognized the privacy problems that came from the requirement of announcing every transaction to the public, and keeping it private.

He had two recommendations to avoid linking an identity with transactions:

- Keep public keys anonymous

- Don’t reuse public keys

This is good advice, but for 1) it is very difficult to keep our identities completely isolated from our payments without extreme caution when making payments online. And for 2) even without public key reuse, if transactions spending from multiple keys are spent together in subsequent payments, it is not too difficult for a tracker to put together which keys belong to which person. These suggestions, even when combined, make for a very difficult to enact and imperfect privacy solution.

After these suggestions, Satoshi then makes a modest mistake, exaggerating the weakness of his own system:

As an additional firewall, a new key pair should be used for each transaction to keep them from being linked to a common owner. Some linking is still unavoidable with multi-input transactions, which necessarily reveal that their inputs were owned by the same owner. The risk is that if the owner of a key is revealed, linking could reveal other transactions that belonged to the same owner.

Satoshi’s assumption, and indeed, all the examples shown so far, presume that all the inputs in a transaction belong to the same owner. In other words, it assumes all the “bills” come from your wallet, which is a fair assumption, but one that isn’t necessarily true. This assumption is called the common input ownership heuristic. It is almost always true for any given transaction, and it is the basis of chain surveillance.

Coinjoin

In early 2013, Gregory Maxwell played a fun game in the bitcointalk.org forum. He provided one of his UTXOs (worth 1 BTC) and an address of his, and asked people to create new transactions using that UTXO as an input. If they proposed a transaction where they sent less than 1 BTC back to him, that meant they were trying to take from him, if more, they were giving to him. If they used the transaction to send exactly 1 BTC back to him, however, they were simply using his address in the transaction to increase privacy by making it look as though it was one of the spender’s UTXOs, even though it wasn’t. When one of Maxwell’s inputs was consumed and sent back to one of his addresses, he posted another one so someone could continue the game. From the perspective of a chain analysis company, this would have the effect of making Maxwell seem rich! Since his address was public, and many UTXOs were being used to construct transactions involving him, anyone analyzing the transactions and making the assumption that all inputs in a transaction were owned by the same person would think Maxwell was transacting with far more bitcoin than he actually was, hence the post’s title: “I taint rich!“.

Of course, this game wasn’t really private, since Maxwell posted his address in a public forum, but it proved a very important and consequential concept. As Maxwell states:

A lot of people mistakenly assume that when a transaction spends from multiple addresses all those addresses are owned by the same party. This is commonly the case, but it doesn’t have to be so: people can cooperate to author a transaction in a secure and trustless manner.

In a later post that same year, Maxwell formalizes this idea into a concept he called Coinjoin:

When considering the history of Bitcoin ownership one could look at transactions which spend from multiple distinct scriptpubkeys as co-joining their ownership and make an assumption: How else could the transaction spend from multiple addresses unless a common party controlled those addresses?

[…]

This assumption is incorrect. Usage in a single transaction does not prove common control (though it’s currently pretty suggestive), and this is what makes CoinJoin possible:

The signatures, one per input, inside a transaction are completely independent of each other. This means that it’s possible for Bitcoin users to agree on a set of inputs to spend, and a set of outputs to pay to, and then to individually and separately sign a transaction and later merge their signatures. The transaction is not valid and won’t be accepted by the network until all signatures are provided, and no one will sign a transaction which is not to their liking.

This means that, in effect, an arbitrary number of people can coordinate to create transactions each contributing and signing their own inputs, without risk of theft by others at any point.

He then highlights another benefit of Coinjoin transactions, which is that transactions can be batched to save on fees by finding someone else who wants also wants to make a payment at the same time as you:

The idea can also be used more casually. When you want to make a payment, find someone else who also wants to make a payment and make a joint payment together. Doing so doesn’t increase privacy much, but it actually makes your transaction smaller and thus easier on the network (and lower in fees); the extra privacy is a perk.

And finally, Coinjoin is a protocol such that, if enough people use it, everyone wins, resulting in privacy gains for everyone:

Such a transaction is externally indistinguishable from a transaction created through conventional use. Because of this, if these transactions become widespread they improve the privacy even of people who do not use them, because no longer will input co-joining be strong evidence of common control.

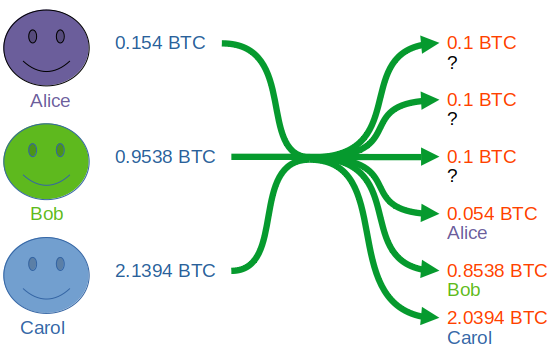

To provide a concrete example, say we find three people who want to do a coinjoin. Beforehand, they agree to mix 0.1 bitcoin, gaining privacy by having three equal-sized outputs to make it unclear which address owns which coins. The change addresses will be clear to an analyst, but the 0.1 values will not.

The privacy gains aren’t necessarily very strong with only three participants, especially if the other participants de-anonymize in later transactions by tying them to their identity, but this can be mitigated with multiple rounds of coinjoin on those coins or by using larger anonymity sets.

To summarize, Coinjoin is a transaction created with inputs and outputs from multiple parties, such that it is difficult to tell who owns which coins after the transaction.

For a deeper dive into how to actually create a Coinjoin and what tools are available, see this guide.

Coinjoin is one of the most effective and widely adopted privacy solutions for Bitcoin today, but it has some major drawbacks:

- Interactivity: Coinjoin requires a high degree of interaction from the participants; they need to agree to a uniform output size and must all supply their signatures within a reasonable time. High interactivity requirements create friction for users, and therefore hinder adoption by wider audiences.

- Centralized coordinators: Wasabi and Whirlpool are currently the most popular methods of Coinjoining. They take fees for conducting the coordination, in addition to the miner fees paid just to participate in the transaction (since Coinjoin transactions have a lot of signature data, they are more expensive). JoinMarket is an example of a non-coordinated service, but this has the tradeoff of increased interactivity.

- Multiple rounds required for enhanced privacy: To get better privacy, it is often recommended to Coinjoin multiple rounds due to the limitations of small anonymity set sizes, which costs time, increases interactivity, and costs more in fees.

- Coinjoins look different from normal transactions: Coinjoin transactions have a distinctive, recognizable pattern: multiple inputs from multiple parties resulting in multiple _uniformely sized_ outputs. This means that if your coins have been identified prior to you doing the Coinjoin, the snooper will know you've Coinjoined. They may not know where the money went or what you do with it after you Coinjoin, but they know how much you had and that you did a Coinjoin in the first place.

Clearly, this is not an end-all be-all solution for Bitcoin privacy due to these limitations, especially for more passive Bitcoiners who want a privacy-by-default approach.

After a few years, a better solution was on the horizon, one that could be done without any extra steps having to be taken by the transactees, was directly peer-to-peer with no centralized coordinators or marketplaces (therefore saving time and money), and looked no different from normal transactions: Payjoin.

Payjoin has been developed from a series of earlier innovations, let’s take a look at those.

BIP-21

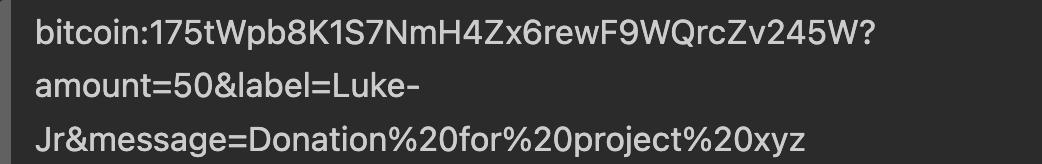

An important user experience (UX) improvement in early Bitcoin was BIP-21. BIP stands for Bitcoin Improvement Proposal, and defines a set of standards that either require consensus changes to the Bitcoin protocol (e.g. hard forks or soft forks) or provide information and methods otherwise useful to interacting with Bitcoin.

BIP-21 is a standard that defines a scheme using URIs to simplify user interaction with Bitcoin, allowing them to pay by clicking links or scanning QR codes. A few query parameters, such as amount, label, and message are also defined so that client software can easily access and parse them for better UX. Here is an example BIP-21 URI with those parameters:

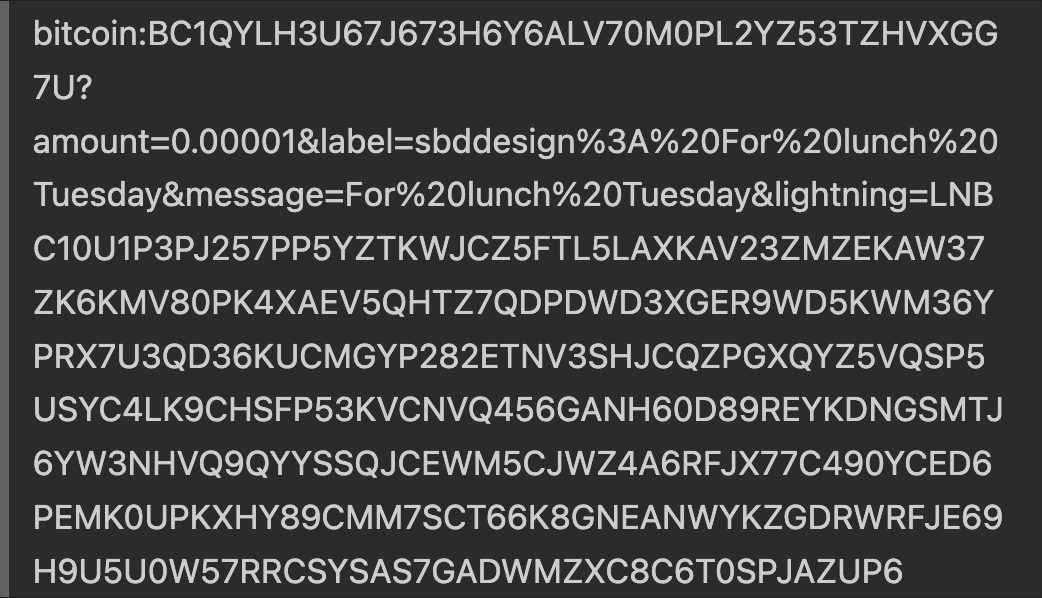

Importantly, the standard is extensible, as custom query parameters can be created and new standards can be built on top of it. For example, in the Lightning Network, the custom parameter lightning can be added in addition to the Bitcoin address so that the user can pay with either method:

This powerful and flexible BIP would prove useful in combination with concepts from Coinjoin.

Pay-to-Endpoint (P2EP)

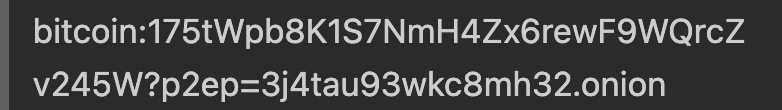

The earliest mention of the Payjoin concept I could find was by Blockstream, published in August 2018, where the article references a workshop from which the concept emerged. It referred to the resulting idea as Pay-to-Endpoint (P2EP), because it combined the concepts of Coinjoin and BIP-21 to allow a sender and a receiver to collaboratively contribute inputs to a transaction via a BIP-21 compliant endpoint provided by the receiver. Here is an example given in the article of what an endpoint provided by the receiver may look like:

Of note in particular is the p2ep parameter, whose value is an endpoint (in this case a .onion address, but it could just as easily be an http:// address or any other compatible endpoint), which signals to receiving wallets that the sender would like to try a P2EP payment. If that fails, wallets should fall back to the sender paying the address normally, just using the sender’s inputs.

Because the contribution of inputs are collaborative in P2EP, and don’t result in the “coin-tainting” uniform outputs that Coinjoin creates, Payjoin transactions are much more difficult to identify.

The idea was a major step in the right direction, but the idea was still nascent and unformalized, and had some additional complexity to be removed.

Aside - Satoshi’s Pay-to-IP (P2IP)

A variation of this idea, called Pay-to-IP, was actually implemented by Satoshi in the very first version of Bitcoin. There were, however, major privacy concerns with this approach, and so it was abandoned in subsequent versions of Bitcoin.

Bustapay

Later that same month, Ryan Havar emailed a revised version of the idea to the Bitcoin developer mailing list, and formalized it into a BIP which he called Bustapay. This version simplified the initial P2EP protocol and removed some of the complexity in favor of simplicity, the idea being that simplicity would prove essential for adoption.

The Bustapay proposal still had a few major issues that needed refinement, and the protocol was not as refined as it could have been. But it was a further step in the right direction, and its focus on simplicity for the purposes of wallet integration was a key one, especially for the slow-moving and cautious Bitcoin developer ecosystem. Although Bustapay never took off, it was a final precursor to the Payjoin proposal we have today, which is ripe for wallet integration, and positive transformation of on-chain transactions.

The Payjoin Proposal

Finally, by mid-2019, the concepts for Bustapay and P2EP were further refined and added to by Nicolas Dorier, founder of BTCPayServer, and Kukks, with the publication of BIP-78, titled “A Simple Payjoin Proposal”.

With our background of the protocols leading up to payjoin, the meaning and purpose of the opening abstract of the proposal should now be clear:

This document proposes a protocol for two parties to negotiate a coinjoin transaction during a payment between them.

This proposal laid out, in much more rigorous detail than prior methods, how to conduct a coinjoin transaction between a sender and a receiver in a way that breaks the common-input ownership heuristic that is simple, flexible, and cheap.

How Payjoin Works

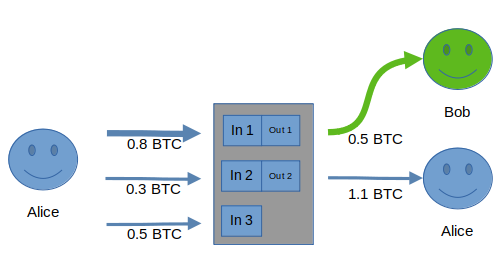

Let’s say Alice wants to pay Bob 1.1 BTC, and a chain surveillance company sees a transaction like this:

They might assume that Alice paid Bob the 0.5 BTC output and gave the rest to herself as change, like this:

And the vast majority of the time, they’d be right! After all, normally the change is the larger amount, and 0.5 is more “round” and thus likely to be used for payment, than 1.1.

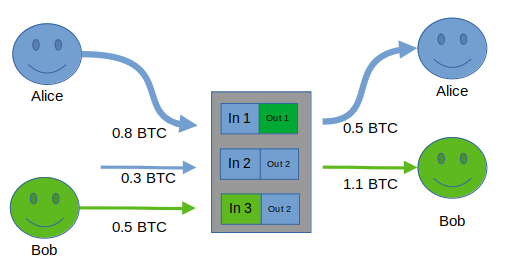

They might also wonder why she used an unnecessary input (the 0.8 and 0.3 BTC inputs would’ve sufficed), but they can never know for sure that this wasn’t a normal transaction, and they can’t know for sure why an extra UTXO was used. She could have just been consolidating a UTXO for easier management later. It could be a payjoin, but even if you assumed it was, which UTXO’s are Alice’s and which are Bob’s? It’s impossible to know. Since most transactions aren’t payjoins, they’ll probably make the faulty assumption that it wasn’t.

Alice, however, is smart and wants to preserve her privacy, and she knows about payjoin, so she asks Bob to contribute one of his own inputs to the transaction. Bob agrees, so he creates a transaction that spends one (or more) of his UTXOs as an input, and proposes it to Alice. If the transaction looks good to Alice, she broadcasts the payjoin transaction to the network. In this case, the transaction actually looks like this:

If chain surveillance made the assumption that both inputs were owned by Alice (as they did in the first example, and currently do in practice), their assumptions about what both Alice and Bob own would be wrong!

It’s also interesting to note that Alice and Bob conducting this transaction helps everybody gain privacy. Because, unlike coinjoin, it looks like a normal transaction, if enough people use payjoin chain surveillance will be unable to trust whether any transaction is normal. By foiling chain surveillance’s attempts at spying on their transaction, Alice and Bob make every transaction a little bit suspect. If there are enough people doing it, it makes them all suspect. Online privacy is often a numbers game, and the more people participate, the better the privacy.

In this example, Alice and Bob collaborated to create a transaction that used both of their inputs to preserve privacy. Now, of course, this whole process can be automated (and is in practice).

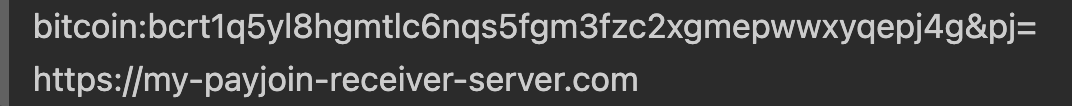

In BIP-78, the process is more formally defined as follows:

- A receiver shows the sender a BIP-21 URI with a query parameter

pj=that refers to an endpoint/server people can send partially signed bitcoin transactions (PSBTs) to. The endpoint can be HTTPs, .onion, or any other authenticated encryption protocol. For example:

The sender creates a finalized, broadcastable PSBT using only their own inputs that is fully capable of making the required payment, to the receiver’s endpoint. This is called the “Original PSBT”.

The receiver modifies the PSBT to include his own inputs, signs his inputs, and gives this back to the sender. He does not modify any of the inputs or outputs of the sender. This is called the “Payjoin Proposal”.

The sender verifies the proposal, re-signs her inputs to finalize the transaction, and broadcasts it to the network.

If something goes wrong at any point in the process, such as, for example, the receiver doesn’t have any UTXOs with which to create the Payjoin Proposal, then the receiver simply broadcasts the Original PSBT and it goes though as a normal transaction. Although this uses all inputs from the same owner, again, if enough people are using payjoin, it becomes impossible to make the assumption that the two parties didn’t payjoin, and surveillance will simply have to assume they did and try to find other methods of tracking payments.

Payjoin’s Many Benefits

More Broken Surveillance Heuristics

The common-input ownership heuristic is not the only privacy-destroying assumption that payjoin breaks. BIP-78 identifies two other heuristics that can be used to identify owners:

Change identification from the

scriptPubkey:In Bitcoin,

scriptPubKeyis the “locking script” that specifies the conditions under which Bitcoin can be spent. It’s calledscriptPubKeybecause the locking condition requires a valid signature matching the public key (the address) to unlock it. In other words, only the person who controls the private key to a particular UTXO’s associated public key can unlock it.There are multiple types of

scriptPubKey’s in use, (P2PKH, P2WPKH, P2SH, P2TR). Typically, wallets use the samescriptPubkeyfor all transactions, and therefore, the change amount (the amount the sender sends back to themselves after consuming UTXOs as inputs) will likely have the samescriptPubkey, while outputs sent to the receiver are much more likely to have a differentscriptPubkey. This means that UTXOs with the samescriptPubkeyin a transaction can be identified as likely belonging to the spender, assuming the outputs sent to the receiver are different.BIP-78 specifies a method to allow the receiver to only use

scriptPubkey’s matching the spender’s, breaking the above heuristic’s ability to tell which outputs are the change outputs.Change identification and payment from round payment amounts:

Normally, payments made to peers have round amounts since it’s far more natural to transact with round numbers. If Bob is charging Alice (and they aren’t basing the bitcoin price on a direct conversion to a “rounder” fiat price), he’s more likely to charge her an amount like 0.00010000 as opposed to a non-rounded amount like 0.00010231, for simplicity. For transactions in which only one output is round, it’s very likely the case (for now) that the non-round output is the change output.

Payjoin also allows for this metric to be broken by describing a way for the receiver to add extra round outputs when constructing the proposal.

Asymmetric Gains by Uniting with a Bigger Crowd

As mentioned earlier, one of the main drawbacks with coinjoin from a privacy perspective is that: 1) coinjoins are easily distinguishable from other transactions and 2) few people do them relative to non-coinjoin transactions. This creates problems for the fungibility of Bitcoin, because it’s possible for people to mark coins as tainted, since some may have the ludicrous perception that the desire for privacy implies malicious intent. Of course, as most transactions, or even a threshold of transactions, preserve privacy, then they cease to stand out.

Payjoin appears like any other transaction, and therefore doesn’t draw attention. An external observer has no reason to even look at a payjoin more closely, because the payjoin shows no effort to obfuscate the payment and change amounts.

By appearing like any other transaction, even marginal gains in payjoin adoption mean that everyone’s privacy is harder to invade, because surveillance heuristics quickly become unreliable. Adam Gibson, a foundational contributor to JoinMarket and an expert in Bitcoin privacy, sums it up well:

If you’re even reasonably careful, these PayJoin transactions will be basically indistinguishable from ordinary payments. […] Now, here’s the cool thing: suppose a small-ish uptake of this was publically observed. Let’s say 5% of payments used this method. The point is that nobody will know which 5% of payments are PayJoin. That is a great achievement […], because it means that all payments, including ones that don’t use PayJoin, gain a privacy advantage!

UTXO Consolidation

Clearly, payjoin and it’s predecessors were aimed at solving privacy problems. But there is a nice ancillary benefit to using payjoin, specified right in BIP-78 itself: UTXO consolidation.

Satoshi’s suggestion to use a new address for every received payment results in user’s wallets having many UTXOs to manage. When these UTXOs are all used together as inputs to new transactions (and assuming it’s not a coinjoin or payjoin), these transactions cost more in fees. Fees are calculated based on the size of the transaction in bytes, since block space is the scarce resource, so more inputs equals more fees for a single large transaction.

It should be noted that using payjoin for UTXO consolidation does not necessarily save on fees, because the expense of each UTXO for chain space still needs to be paid at some point. Rather, it spreads the fees out over time and gives an opportunity to batch the UTXO with the payment. Batching makes UTXO consolidation cheaper than doing it as its own transaction. It also makes for easier management of UTXOs, and less data stored on disk. In addition, it is possible for wallets to implement a way for a receiver to specify that they would like to consolidate their UTXOs when mining fees are low in advance, making UTXO consolidation an automatic and smoother process.

Lightning and Payjoin: A Perfect Match

Opening Lightning Channels with Payjoin

The Lightning Network (LN) is a second-layer solution built on Bitcoin that takes transactions off-chain to allow for near-instant, final settlements with far lower fees, tremendously increasing transaction throughput, improving privacy, and allowing for new use cases for Bitcoin such as micropayments. It uses a network of payment channels between nodes to route payments from source to destination. These channels require node operators to lock up “liquidity” (bitcoin that can flow between one node and its channel partner) between their channel partners. How much bitcoin you can spend in a channel is limited by how much liquidity exists on your side of that channel.

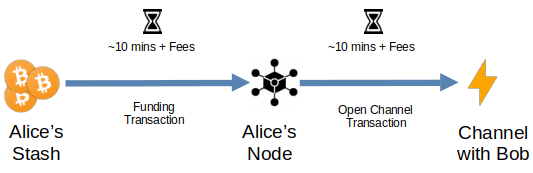

Most of the complexity in managing a lightning node comes from opening these channels and managing the liquidity in them. Onboarding is one of the biggest pain points, since there are several steps involved. Let’s say Alice wants to open up a channel with Bob and she has setup a brand-new, unfunded lightning node. Alice has to do the following:

Send an onchain transaction funding her newly created lightning wallet with sufficient funds to at least open the channel and wait (at least 10 minutes) for it to be confirmed.

Use her lightning wallet software to negotiate a channel opening transaction with Bob and wait for it to be confirmed.

At a minimum, Alice has to pay two fees and wait ~10 minutes per transaction, which can be tedious.

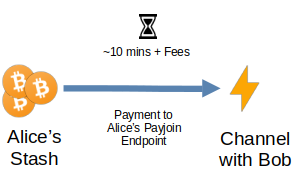

Payjoin can simplify this process and help Alice save money by doing both the funding and the opening transaction at once.

In this scenario, Alice preconfigures her payjoin receiving endpoint with the details of how she’ll open channels: including the amount of bitcoin and which channel partners she’ll open to. Then, using a wallet with payjoin support, someone (presumably Alice) will send a payjoin proposal, negotiate the payjoin transaction with the receiving endpoint, and upon receiving the funds, the endpoint will make the necessary API calls to open a channel with Bob’s node.

In other words, the sender (probably Alice in this case) will send a payjoin proposal to Alice’s receiving payjoin endpoint to create a transaction that pays directly to the 2-of-2 multisignature output between Bob’s node and Alice’s node to construct a lightning channel between them. Which turns the process into a one-step transaction:

One interesting thing to note is that both LN and payjoin currently have a liveness requirement (though, in the case of payjoin at least, perhaps not for long), meaning that participants must be online when transactions take place. This is fairly limiting in comparison to on-chain Bitcoin, which only requires the sender to be online at the time of payment. However, this also allows for the two protocols to pair together quite nicely.

For example, Lightning is great for increasing privacy by taking payments off-chain, and for massively increasing Bitcoin’s ability to be used as a medium-of-exchange (i.e. something you would actually use to buy everyday things) in addition to a store of value. But the requirement to open channels on-chain means that the size of your channels and the people you open channels to leaves an onchain footprint. For reasons already discussed, payjoin can obfuscate and destroy many assumptions made by snoops.

It also makes things simpler because users now only have to make one payment instead of two to open their first channel, faster because they only have to wait for one transaction to be confirmed, and cheaper because they only have to pay one fee. In fact, more than one channel can be opened by these means. What if you could make a list of all the nodes you wanted to open channels to, make a single transaction to a BIP-21 payjoin receiving endpoint, and have them all open at once, automatically, waiting for one transaction to confirm and paying one fee. For all your channels. Well, you can!

There is already a project which implemented this idea, called Nolooking, which allows you to queue up a list of public keys and batch open multiple lightning channels at once! This way, Alice can not only open a channel up to Bob, but she can open up channels to Bob, Carol, and Dina, all the while making just one on-chain payment! Needless to say, the potential for this to simplify Lightning UX is huge. It’s exciting to imagine a future in which Lightning wallets just have payjoin on by default, and the de facto user experience is to just pick your channel partners, make a single Bitcoin transaction, and voila! You now have a lightning node with as many channels as you can afford, and paid one transaction for it. How amazing would that be?

It’s easy to imagine how this could simplify self-custodial lightning adoption. It would be interesting if lightning wallet software could just have a “quick setup” option, where all the user has to do is input how much Bitcoin they can lock up (i.e. how much liquidity they want), set to a default of opening a few, reasonably sized channels with decent tradeoffs for routing and fees. For advanced users, there could be an “I know what I’m doing” option.

Weaknesses

As with any protocol, there are tradeoffs to payjoin.

One of the main issues is the liveness (or online-ness) requirement. The receiver’s payjoin web server must be online at the time the transaction is sent in the current implementation, due to the need for both sender and receiver to negotiate (programmatically, of course) the resulting transaction. This might limit adoption to merchant servers or lightning nodes, as they are the only people with an incentive to always stay online. It would be much more convenient from a user’s perspective if a transaction could be sent at any time irrespective of whether the receiving server is online.

Another less likely but more dangerous weakness is that if a payjoin server (i.e. the receiver’s server) is on an unsecured server, the receiver’s outputs could be modified in flight (before they reach the sender) and stolen.

However, as we’ll discuss later, a solution to the above two problems has already been proposed.

Finally, one weakness of the protocol is simply the fact that it faces adoption barriers as wallets must do the work to integrate it. A particular challenge is that the ideal user interface would be one in which payjoin is just enabled by default. Sending wallets and receiving wallets just try to payjoin without a user necessarily needing to be burdened with setting up that privacy feature. The best privacy is default privacy, since requiring users to take action to defend it means they probably won’t. Therefore, for payjoin adoption to really take off for the average user, it needs to be a seamless experience that they don’t have to think about. Wallets should enable it by default. Remember, it’s built right into the protocol to fallback on regular transactions without requiring any additional action from the user in case the payjoin fails.

Serverless Payjoin

Dan Gould has submitted a draft BIP for a version 2 of payjoin which allows it to be done asynchronously and without using a server. This serverless payjoin would solve both the requirement for a receiver to be online at the time of payment, and the security issues related to this being done on unsecured servers, mentioned earlier. As the always-online nature of payjoin receivers is perhaps the biggest user experience barrier to adoption, the implementation of this BIP could be a huge benefit for payjoin adoption and passive Bitcoin privacy.

The Current State of Payjoin Adoption

As of late 2023, payjoin adoption is still relatively low, but has been steadily increasing since its inception in 2018.1 Since payjoin is ready to use today and doesn’t require any Bitcoin consensus changes, the only real impediment is for wallets to write the software to adopt it, and the tools to help them do so are getting better every day. Payjoin Dev Kit (PDK) is a new payjoin implementation with modules that wallet software can use to integrate today. It even comes with a payjoin-cli tool that allows you to create payjoins from the command line. The library is written in Rust, but bindings allowing other languages to use it are currently being built.

Wallet Support

BTCPayServer and JoinMarket already support both sending and receiving, although not by default. BlueWallet, Sparrow, Wasabi, and BitMask support sending. A few other wallets support it via an extension, including Bitcoin Core. There are active PRs to integrate payjoin into Mutiny Wallet today. See here for the current state of payjoin adoption.

Payjoin and Bitcoin’s Future

As mentioned earlier, Adam Gibson has proposed that even just 5% of on-chain transactions being conducted with payjoin could have a huge impact on Bitcoin privacy. We just need a threshold number large enough that analysis companies can never safely assume they’re interpreting the transactions correctly. Once their methods of spying on us are broken, then ill-informed, arbitrary, and bad-faith restrictions on Bitcoin privacy imposed by those who neither understand its benefits nor have any interest in preserving our right to privacy will become irrelevant.

And as we’ve seen, due to the many possibilities opened up by payjoin’s flexibility, it is not merely a privacy solution, but an extensible cooperative transaction protocol that allows for solutions such as fee reduction and single transaction multi-channel opening for lightning nodes, among others. The benefits it would provide to Bitcoin could be enormous and achieved today without changing anything about Bitcoin itself.

So what are we waiting for?

Support

If you’d like to support or contribute to payjoin’s development, start by joining the discord, donating, or checking out payjoin.org.

Acknowledgements

I want to give a huge thank you to Dan Gould for reviewing and suggesting very helpful improvements to this article.